LPN / LVN History & Background

LPN / LVN History & Background

To gain clarity, let’s explore the history of the LPN/LVN in the United States.

To gain clarity, let’s explore the history of the LPN/LVN in the United States.

Long before there were nursing schools, scope of practice standards and laws, the role of caregiver or nurse was delegated by family and mythical tradition. Even today the “healer” within a family or community still ministers to sick family members or neighbors whether officially licensed as a nurse or not. However, from a historical perspective nuns, monks, and local common women, were designated to minister to the poor and sick. The dark ages saw this trend of mercy from friends or family, but during the Middle Ages Catholic monasteries took on the role of nursing the ill and infirm. With the reformation the church’s role diminished and female prostitutes, thieves, and criminals were compelled into nursing or face prison indefinitely. Often these women had no training as nurses in healing the sick and would often rob, extort, or aid in hasting the death of their charges to further benefit from the spoils left behind. Besides atonement for their deviant lifestyles, there was a more sinister reason behind consignment of these unrepeatable women. In the alarming and staggering death of a plague-ravished population it was thought that if these women were to die it would be no great loss to society. Thus, nursing was viewed as a disgraceful occupation performed by vagrant and scandalous women (Egenes, 2009).

By the 18th century, nursing once again started to evolve into a benevolent profession performed through missions, churches, and hospital deaconesses (nuns) dedicated to caring for the poor and sick. Nonetheless, the common or disreputable woman nurse remained part of the resources of nursing care available for much of the population. Still considered to be a lowly profession, by the 19th century Florence Nightingale would emerge from the aristocracy as the pioneer in reforming nursing from a shameful profession to the beginnings of a science based practice. Before Florence, deaconesses or nurses received minimal education in the practice of nursing. Up to this time, most nursing was learned through oral traditions and folk remedies. These practices often killed rather than healed the illness, but were attributed to spiritual maladies rather than the physical manifestations of illness. Through the pioneering work of Nightingale and others that emerged during this time, nursing began to revolutionize theoretical and clinical practices that became the corner stone of formalized nursing training education (Egenes, 2009).

Much has been attributed to Florence Nightingale and rightly so, but there are numerous women including sisters of the Catholic Church that contributed to the advances of nursing as an educated and trained profession. Although nursing has changed significantly since the time of Nightingale, the need for nurses has shaped the evolution and appreciation for the indispensable role they have played especially in times of war and epidemic outbreaks.

The Emergence of Practical Nursing & War

In the mid-1800s after the Crimea war, the aristocracy of Nightingale’s influence established the first funded school of practical nursing in London. Within ten years the U.S. Civil War began and the need for nurses became dire. The designated nurses that served wounded Civil war soldiers were usually volunteer wives and mothers, or again, Catholic nuns Since Nightingale’s educational model had not been established in America as of yet, none of the volunteer nurses had any formal nursing training. Like the Crimean war, the American Civil war brought the reality for the need to train nurses building on the experience of caring for battle-related injuries and illnesses. Thus, during the latter portion of the 19th century into the beginning of the 20th century, the post-Civil war population and intensified immigration perpetuated the spread of disease in the overcrowded cities propagated by an environment of emerging industrialization. Nursing care was conducted only during daylight hours by unskilled migrant family members or once again by prostitutes, convicts, and substance abusing women.

The appalling conditions of public facilities for the sick staffed by untrained and substandard caregivers caught the attention of concerned charities and citizens. Accordingly the reputation of the success of Nightingale’s London school of nursing that began under her influence piqued the interest of the concerned to establish the first American nursing education programs in New England and Philadelphia. Within a few years hospital training programs for practical nursing sprang up throughout the East coast. However, hospitals in exchange for educating these individuals took advantage of the cheap, compliant student nurse labor force. Students were expected to work twelve to twenty hours in excess of their studies. Upon graduation the practical nurse gained an autonomous and lucrative self-employment working in households ministering to the sick and performing household chores. Very few were maintained in the hospital and even less became trained for specialties such as surgical assistants (Crihfield & Grace, 2011).

The Nurses’ Associated Alumnae of the United States and Canada was created in 1896 and later would be known as the American Nurses Association (ANA, 2015). The reason for developing the organizations was to establish the first licensure standards and nurse practice laws. Simultaneously, the Volunteer Hospital Corp was developed in 1898 to support the Spanish-American War. Finding the significance of education and training the Volunteer Hospital Corp insisted on accepting only licensed nurses trained from one of the innovative accredited nursing schools (Vancouver Island University Practical Nursing Program Guide, n.d.).

By the 20th century scientific discoveries in understanding disease causing organisms and development of modern technological treatments led to the gradual change from educating nurses in the hospital-training model to formal education within institutes of higher learning. The Army Nurse Corp and Navy Nurse Corp were created in 1901 and 1908, as helpful permanent establishments that improved standardized education of practical nurses. Expanding into the troubles of public health, nurses once again began visiting the sick in their homes through the creation of public health nursing organizations. The educated practical nurse was the exemplary hands-on caregiver working in clinics, health departments, industries, and to some extent hospitals. The designation between the registered nurse and the licensed practical nurse was not yet established, nursing in general was autonomous as most of the medical practices. Nurses set their own contracts and rates for the work they offered and the organizations they started.

One of these organizations was the American Red Cross (2015). The American Red Cross was stylized by Clara Barton in 1881 after the Switzerland International Red Cross model that began in 1863. As a fledgling organization the American Red Cross offered disaster relief for many years until 1900 when it became a nationally sanctioned congressional charter. The reputation and assistance the American Red Cross demonstrated became recognized by the Geneva Convention to fulfill the requirements represented by nursing during war time. As a recognized organization, educated practical nurses were recruited to serve in World War I (WWI), educated by the American Red Cross, the US Army Corps, and Navy Nurse Corps.

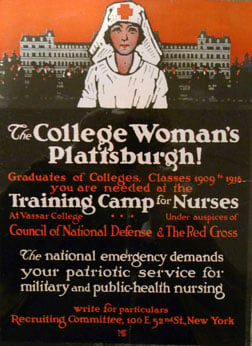

Efforts to supply the need for nurses during wartime was never fully achieved and the need for educated practical nurses remained in demand even after WWI, when the outbreak of Spanish Influenza spread around the world. Again the American Red Cross, supported the innovative development of the Vassar Training Camp for Nurses in New York. The Vassar Training Camp was devised as a method to “fast track” the training and supply of practical nurses. The three month program for college educated women included room and board, tuition, and laundry services. During times of war and the ensuing pandemic of Spanish Influenza emphasized the value of the educated nurse philosophy to cure and care for sick and injured (Mills, 2009).

Efforts to supply the need for nurses during wartime was never fully achieved and the need for educated practical nurses remained in demand even after WWI, when the outbreak of Spanish Influenza spread around the world. Again the American Red Cross, supported the innovative development of the Vassar Training Camp for Nurses in New York. The Vassar Training Camp was devised as a method to “fast track” the training and supply of practical nurses. The three month program for college educated women included room and board, tuition, and laundry services. During times of war and the ensuing pandemic of Spanish Influenza emphasized the value of the educated nurse philosophy to cure and care for sick and injured (Mills, 2009).

The training program through Vassar was very successful in educating and meeting the needs for trained nurses until 1933 when the Great depression closed Vassar’s and several other nursing educational programs. Like most of the population nurses found it difficult to find employment. However, under the Civil Works Service and the Federal Emergency Relief Administration funding for bedside nursing care was paid at a set rate. The funding provided in-home nursing services to the unemployed, as well as public health education and preventive measures. This was the beginning of end of nursing as an autonomous health care service and soon would be structured as an employee-related position (Mills, 2009).

The autonomy that many educated practical nurses achieved prior to WWI continued to gradually disintegrate as the desperate need for nurses again ramped up at the beginning of World War II. As WWII absorbed the available workforce, hospitals and other industries desperate for workers (including nurses), began to offer incentive programs to attract a dwindling labor force. Instead of setting their own fees and salaries nurses were given a wage based on the same structure still used today and endorsed by physicians that valued, but maintained nursing as a subordinate practice to medicine. Nursing organizations along with the American Red Cross recruited nurses through the development of the Nursing Council of National Defense and the United States Cadet Nurse Corps program. A lack of supply and a great demand again called for educational programs that would crank out nurses in accelerated programs. In exchange for serving in the military or as a civilian nurse, student nurses were provided uniforms, tuition, monthly stipends, books, and housing during a thirty hour or less monthly training course. However, nurses serving during the time of war began earning a reputation of positive respect from the general public in spite of the wages that were often lower than the average hotel maid or seamstress. In 1941, the National Association for Practical Nursing Education and Service (NAPNES, 2015) was established and by 1945 became the first accrediting agency for practical nurse training programs (Dictionary of American History, 2003).

The licensing of trained nurses and national boards of nurse examiners did not emerge until 1951 and 1952 under the supervision of physicians. By 1955 all states had developed standards of educational training, regulations, and laws for both the licensed practical nurse and the registered nurse. Nursing exams were standardized based on state-to-state development but not nationally. Yet, many of the post-WWII nurses were expected to quit working once they married and began domestic life as wives and mothers. It would not be until the radical 1960s that nurses would once again emerge into the workforce as working wives and mothers bargaining for better wages. The autonomous structure of the self-employed nurse was now a thing of the past and hospitals were reluctant to improve work conditions or increase wages. Even the ANA did not advocate for nurses since it had implemented a “no-strike” policy that eventually was rescinded in 1966.

The need for caregivers/nurses has been salient feature since there has been human illness. Throughout the centuries changing environments, populations, endemics, and war have influenced the perception, practice, education, and image of nurses. The licensing and establishing standards of care has improved nursing but imposed other limits to shortages and adequate training. Desperation has altered the focus of each of these principles in lieu of supply and demand. In our contemporary familiar society most Americans understand that nursing has undergone a short supply of nurses. During the mid-1980s and most recently at the end of 20th into the 21st century, there are many reasons for these trends that do not involve societal norms for family commitments as in the past. Changing healthcare structures, the aging baby-boom population, expensive technological advances, and aging experienced nursing are just some of the reasons behind the continued predicted shortage of nurses in the coming years.

As always the practical nurse has been the compensating solution to shortages in the past and according to the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME, 2015) union, is poised to become the solution for the nursing demands predicted for the future. Through organizations such as the ANA the standards and suggested entry of practice have always been recommended at higher levels of education, but ignore the practical vision of the demand. Adhering to these nursing organizations recommendations, has reduced the LPN presence in hospitals nationwide. Not only has this created an environment for burn-out among overworked RNs in acute care settings, but it has also created a wedge in the team spirit of nursing. Although the scope of practice for RNs and LPNs remains somewhat different the value of the LPN as a qualified cost-effective health care team member has been minimized in hospitals. The AFSCME recommends that LPNs be employed in the hospital setting and managers become educated on the LPN scope of practice. They also recommend that hospitals support the education of LPNs through standardization of the scopes of practice for all nurses. Considering the historical need of nurses, their contributions, and the opportunities available to the nurses of today.

I would agree that the traditional practical nurse (LPN) continue to be the standard bearer of nursing’s legacy. – Lucinda Lasater

References for LPN History (Non-Internet)

Crihfield, C. & Grace, T. (2011). The history of college health nursing. Journal of American College Health, 59(6).

Egenes, K. (2009). History of nursing. In Issues and Trends in Nursing: Essential Knowledge for Today and Tomorrow, Gayle, R. & Halstead, J (Eds). Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett.

Related Articles

- Most Affordable LPN/LVN Programs for 2026: Your Path to Nursing Success on a Budget

- LPN / LVN History & Background

- LPN to RN Bridge Programs: Accelerating Career Growth for Practical Nurses

- You Will ALWAYS Be Learning!

- Nursing in Long Term Care

- Full Time Mother and LPN

- Culture of LPNs and RNs in Team Nursing

- How to Prepare for Your LPN/LVN Program Entrance Exam